honeydew buddhist wall painting 甘露幀畫

Goryeo's pattern 高麗文樣

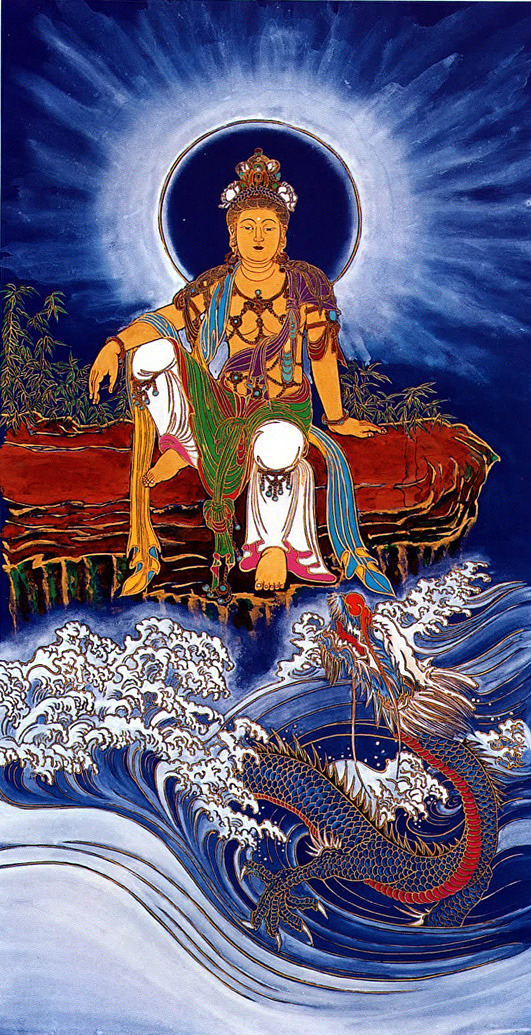

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva 金泥彩色觀音

Paradise picture 極樂圖

chrysograph Avalokitesvara 金泥觀音

chrysograph Avalokitesvara 金泥觀音

chrysograph Avalokitesvara 金泥觀音

chrysograph Avalokitesvara 金泥觀音

chrysograph Avalokitesvara 金泥觀音

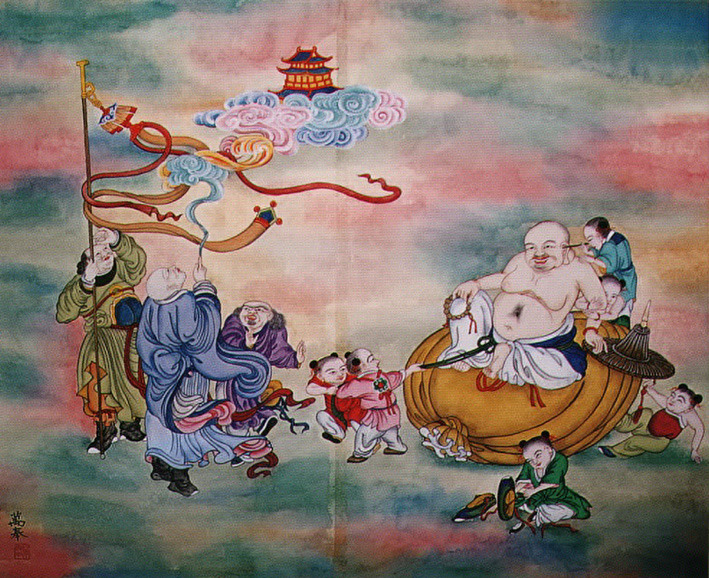

Arhat pictures 羅漢圖

Bosal-Do 菩薩圖

Fenghuang Dancheong 鳳凰丹靑

Fenghuang picture 鳳凰圖

sangdan Tanghwa 上壇幀畫

a rabbit 十二支神像

a hen 十二支神像

Arhat section drawing 18羅漢部分圖

Arhat section drawing 18羅漢部分圖

twin dragons 雙龍

|

twin dragons 雙龍

Yonglakdo 瓔珞圖

Yeongsanhoesang-do 靈山會相圖

Arhat drawing 58 羅漢圖

Arhat section drawing 58羅漢部分圖

Arhat section drawing 58羅漢部分圖

white porcelain 靑華白磁

white porcelain 靑華白磁

white porcelain 靑華白磁

7 stars buddhist wall painting 七星幀畫

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Avalokitesvara sea 海上觀音

Arhat 十六羅漢

Arhat 十六羅漢

Arhat 十六羅漢

Arhat 十六羅漢

Arhat 十六羅漢

Venerable ManBong

Korea takes pride in the preservation of its culture, and the government in recognition of its rich heritage officially designates certain people and places as national treasures. At 77, Lee Man Bong is Living Treasure of Korea No. 48 and one of his country's masters of Buddhist art.

Lee, a Buddhist monk, whose home is Pomun Temple in Seoul, began his art career influenced by a fortune teller's prophecy that he would be a Buddhist monk. In 1917, at the age of 7, he joined the T'aego order, one of the two major Korean Buddhist sects. At 16 years of age, he was apprenticed to the venerable Kim Ye Woon who taught him to become an expert in two forms of Korean Buddhist painting, Tanch'ong and T'aenghwa. Today, Lee's works can be seen at more than 170 of Korea's Buddhist temples and cultural landmarks throughout the country.

Whereas most painters acquire skills to express individualistic ideas, Lee pursues his art as an act of religious faith. He says, "Each time I pick up a brush, I paint with the heart of a Buddha." Early this summer, fourteen of his Tanch'ong and T'aenghwa paintings were exhibited at the Korean Cultural Service gallery under the auspices of the Korea Society, the Korean Cultural Service and the Korean Artists Association of Southern California.

Lee, who, with his son, the venerable Lee Yong Woon, presented a slide and lecture presentation on Buddhist painting, says, " Tanch'ong painting does not express the artist's world. Rather the inspiration comes from one's feeling toward the Buddha."

Ven. Manbong

By his own account, my teacher Ven. Manbong was awestruck the first time he gazed up at temple art, and he decided there and then that he wanted to do Buddhist art for the rest of his life. Soon after becoming a novice for monkhood, he began his long journey to becoming Korea's foremost Buddhist artist of the century. That was around 1920.

On August 1, 1972, along with two other monks -- the late Ven. Ilsop and the late Ven. Wolju -- he was given the title (commonly called "Living National Treasure") of "Preserver of Intangible Cultural Property No. 48, Tanch'ong.". Tanch'ong, literally "red-blue," is the term for colorful cosmic patterns and designs on temples and other important buildings. In a broader sense, it is the traditional term which encompassed all Buddhist temple painting.

Ven. Manbong did not hold his first local exhibition until 1989. The early 1990s brought with them two exhibitions in Japan, an unprecedented number of major domestic projects (including those for two new halls at Pongwonsa, and huge paintings for Kakwonsa in suburban Chonan and for the Army Headquarters Dharma Hall at Mt. Kyeyong), and two pottery & painting exhibitions in Seoul in 1993. Then in October 1998, as he neared his 89th birthday, Ven. Manbong received the much-deserved Order of Cultural Merit Silver Crown, the highest possible cultural award given by the Korean government.

People appreciate Ven. Manbong not just for his tremendous artistic abilities and his lifelong dedication to one pursuit. As a personality, he's one-in-a-million. Despite his prestigious rank, he is genuinely humble. In the Mahayana tradition, he usually prostrated simultaneously to anyone who prostrated to him, at least until he injured his hip in the mid-1990s. Also, he has never been heard to boast. And he indeed lives up to his name, "Ten-thousand Services," by serving all: Literally millions have chanted and practiced before, and been inspired and comforted by his paintings over the decades. Yet Ven. Manbong took as much pleasure in feeding dried cuttlefish to his now-departed pet duck and the neighborhood dogs as he did in his work. He evidently once held a 49th-day memorial service for a pet cat which had died from eating rat poison somewhere (interesting retribution!).

Ven. Manbong's face glows with his genuine warmth. His unpretentious laugh is as delightful as his auspicious "tiger" eyebrows which spike out from his head. His generosity abounds: While he may accept large fees from wealthy establishments, the money is well dispensed on others, including the building programs at Pongwonsa, and sometimes he gives away works to places with little leeway.

While he overflows with hilarious stories from yesteryear, he never talks about himself; yet stories about him are numerous, and they reveal much. One from the Korean War (1950-1953) is worth mentioning.

During the war, a huge firefight broke out on Mt. Ansan above Pongwonsa. In the middle of the fracas, the Main Buddha Hall caught fire, and while others on the compound were scurrying for their lives, Ven. Manbong dashed into the burning hall, dodging crossfire, to retrieve the statue of Buddha. Many attribute this single act to his health and longevity. He has never told the story.

His tremendously sharp wit complements his sharp mind. One hot summer day, he spotted a student's white fan. He called out for some watercolors, lay down in his favorite leisure position of right ankle atop raised left knee, and painted a classic temple-in-the-mountains scene on the fan that was held at left-arm's length above his face. He finished in 15 minutes. Yawn. He then took a nap.

Enter his cronies, other elderly monks at the temple. They drop by frequently, and Ven. Manbong is funniest when they're around. He woke from his nap to chat, and one of his friends said that the painting on the fan was so fantastic that the fan shouldn't be used because it would soon become tattered. Ven. Manbong thought for a moment and came up with the perfect solution. He told the student to take the fan home, hang it spread-out and upside-down over a doorway between rooms, and then just run back-and-forth under the fan whenever hot.

Although little known to the outside world, the rich tradition of Korean Buddhist art is alive, well and even enjoying a revival as more and more young people look the tradition as both a skill and a means of Buddhist practice. In fact, the traditional course of becoming a "Gold Fish" (i.e. a recognized professional Buddhist artist) was, in the old days, as much of a means of becoming enlightened as it was of preserving and promoting the great art tradition. The traditional course was a rigorous 20-year one that involved tracing, drawing and free-hand sketching a total of 3,000 copies of each of three line drawings -- a King of Bardo, a Guardian and a Bodhisattva -- and combining this with Sutra study at night. The rush and instant demands of modernity have done much to upset that tradition; yet some of modernity's conveniences, such as the Xerox machine that can size line drawings to perfection, have guaranteed the swifter proliferation of more Buddhist paintings. And while in earlier centuries Buddhist painting was almost exclusively limited to monks, today the art has been taken up by large numbers of lay people, including a formidable number of women, something that would have been unthinkable in a staunchly Confucian Korea even a decade ago.

Today, many artists are continuing with the traditions found in the late Choson Dynasty (1395-1910), since most of the existing line drawings survived from that period through a Japanese Occupation and the Korean War. Others artists are seeking new styles to meet the needs of modernity, although the contents of temple paintings leave little leeway for innovation. Only time will tell whether some of today's works will stand in the future as masterpieces, like some of those still remaining from Korea's heavily Buddhist Koryo Dynasty (935-1392) or the heavily Confucian Choson Dynasty (1395-1910).

The Korean Buddhist art tradition has its roots of course in the Ajanta caves in India. That tradition traveled along the Silk Road and proliferated in the sacred Caves of the Thousand Buddhas in China, eventually reaching Korea. Chinese culture heavily influenced Korean culture for many centuries throughout history, and Buddhist art was no exception. Even today, Chinese line drawings are greatly prized and admired, but Koreans do what comes naturally to people everywhere add local flavor to the imported culture. And during the Choson Dynasty, when Buddhism was largely banished to the countryside, a fascinating mixture of folk art and Buddhist art took place, leaving an indelible Korean flavor to the imported traditions.

Materials have changed with the times, too. In the olden days, imported mineral paints were used on natural silks, paper or hemp. Around the turn of the century, cotton became more common "canvas" for temple paintings, and prohibitively expensive mineral paints were gradually replaced by imported and domestic chemical paints. Older paintings done with natural materials have lasted hundreds of years, but today's works may not even last 100 years.

Canvases are fixed with a diluted glue, comparable to carpenter's glue in the West; line drawings for the particular painting are traced in India ink onto the canvas; mulberry paper is applied to the back of the canvas to provide firmness and to prevent bleeding; and then the painting process begins. The paints themselves are mixed with hot water and more glue as fixative. Broad areas of colors are done first, followed by more detailed areas. Any given color may be applied two or three times in a layering sequence, and there has been a definite order of color application. Secondary colors are applied, the line drawings are retraced in ink, and other details, such as clothing patterns and designs are applied. While those not in the know tend to scoff at the process as "paint by numbers," the process requires intensive training, concentration and memorization. Facial features are the very last to be applied, since they are the most important. According to Buddhist tradition and belief, once the eyes are dotted, the figures transform from mere iconography into incarnations. Buddhist artists are often referred to by others as "Buddha Mother," because in this way of painting and dotting the eyes they give birth to new Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

Built-in Buddhist Teachings:

The Invisible Through the Visible

It is in this very process of producing the visible that one learns the invisible. A number of Buddhist teachings are built into the learning/painting process, and artists, often unconsciously, absorb these teachings into their attitudes and behavior.

Respect and humility are part of the traditional course. Traditionally, students sitting on the hypocaust floor in the lotus position are supposed to make a half bow before starting each tracing, drawing or painting. This helps to develop a healthy respect for everything in the universe as well as for the sacred work itself. It is, however, an easy habit to fall out of and is rarely seen today except in very devout beginners.

The equality of everything as espoused by Buddhism is taught through the mastery of the most common temple painting line, the "vertical line" which is equally thin (or thick) from top to bottom throughout the entire painting. This line is hard to master at first, but practice, and lots of it, makes perfect. One of the main purposes of doing thousands of copies of the King of Bardo is to develop this skill. Abdominal breathing and holding the breath while drawing the line help to maintain clarity of mind and draw a steady line. These equal lines can be found even on the early Tunhuang cave murals in China and they were among a variety of line types perfected by the 8th century Tang court superartist Wu Taotze, who's highly stylized drawings set the pace for all future Chinese, and eventually Korean, Buddhist paintings.

Zen's "Beginner's Mind" is essential to maintaining sanity through several thousand tracings and drawings, and to incorporate concentration on the present, the Buddhist constantly-flowing NOW. Just the thought of several hundred more tracings can be discouraging. But each one is a new beginning, each moment carries with it new potential. The student must forget the past (which exists only in memories) as well as the future (which is only a concept) and concentrate on the present work. Perfectly equal lines can come only from such perfect concentration on the present. In addition, this beginner's mind, when transferred to activities outside the studio, can do wonders for one's life: fewer biases and preconceptions, and greater openness to each moment and each person make life much easier.

This beginner's mind, and concern with the now, is also related to the Buddhist emphasis on process rather than result. By dwelling on future results, one can easily lose sight of what one is doing. Concentration on the process is essential: good processes naturally bring good results, and each result, in a larger perspective, is also both a cause and a process. All nows are process. From the Buddhist perspective, everything in the universes, including you and I and humanity as a whole, is process.

The essential Buddhist teaching of non-attachment (not to be confused with indifference) is also easily found in the course, and this, too, is related to beginner's mind and the importance of the eternally flowing now. After each 1,000 tracing, the student is told to go out into the yard and make a nice fire out of them. No time for sentimental ego clinging. This also reinforces humility -- the awareness of the fact that in such an astounding, infinite cosmos, these tracings are everything yet nothing. This non-attachment, combined with the Buddhist teaching of selflessness, accounts for the fact that so many old paintings have no signatures: the painting and its teachings are important and the artist is nonabiding.

Patience is an obvious ingredient to eventual success, and although patience is valued everywhere, it is one of the Six Perfections of Mahayana Buddhism. This patience often can be secured by seeing one's own place in the much larger picture, by seeing each day as part of an infinite continuum.

Physical and mental purity are also essential to concentration and good religious art. Ven. Manbong claims that in the old days he had a separate set of clothes to wear to the toilet, and upon returning he not only washed again but brushed his teeth and gargled, which he still does. He claims that this is also an effective method of preventing colds. The course is also good, through patience training, for melting down the "Three Poisons" of avarice, aversion and foolish thinking, the later of which includes the notion of a separate self. As a natural result of immersion in the course, one comes to dwell on the interdependence of everything as one works with a host of materials that are the direct and indirect products of literally thousands of people; skills passed down by thousands of artists for hundreds, even thousands of years; folk and religious systems developed and redeveloped by millions of people and myriad cultures, all intertwined. Even the production, processing and preparation of the food taken each day to provide the energy to work is the result of incalculable efforts by innumerable people. One eventually reaches the Mahayana Hwayan conclusion of "all in one, one in all." This is all part of the process of discovering the Cosmic Self as opposed to the egocentric self. It is only from the egocentric self that the three poisons, and consequently suffering, arise.

MAY ALL BEINGS BE WELL AND HAPPY!!!

B r i a n .B a r r y

Buddhist Painter.and .Dharma .Instructor

bbbudartist@yahoo.com