The Worthy One: A Comprehensive Study of the Arhat

I. Introduction: The Pinnacle of Perfection

In the vast and intricate landscape of Buddhist philosophy, few figures command as much reverence and doctrinal significance as the Arhat (Pali: Arahant; Sanskrit: Arhat; Korean: 아라한/나한). The term denotes a being who has reached the ultimate goal of the spiritual path: the complete cessation of suffering (dukkha) and the attainment of Nirvana.

An Arhat is not a god, nor a mythical savior, but a human being who has engaged in the rigorous mental and ethical discipline taught by the Buddha to purify the mind of all defilements. Having destroyed the causes of rebirth, the Arhat stands as a testament to the potential of human consciousness to transcend conditioning and achieve absolute liberation.

This document explores the etymology, the stages of attainment, the psychological profile of an Arhat, the divergence in views between Buddhist schools, and the cultural legacy of these "Worthy Ones."

II. Etymology and Definition

To understand the Arhat, one must first understand the word itself. The term is rich with linguistic duality, offering two primary interpretations that define the nature of this spiritual status.

1. The Worthy One (Arhati)

The root arh implies worthiness or merit. In this sense, the Arhat is "The Worthy One"—a person deserving of the highest offerings and respect from gods and men because they have embodied the highest ethical and spiritual standards.

2. The Slayer of Enemies (Ari-han)

A popular folk etymology in the Buddhist commentaries breaks the word into ari (enemy) and han (to kill). Here, the "enemies" are not physical foes, but the inner demons of the mind: the Kilesas (defilements).

- Greed (Lobha)

- Hatred (Dosa)

- Delusion (Moha)

Thus, the Arhat is the "Slayer of the Foes," the warrior who has conquered the internal battlefield and emerged victorious over the instinctual drives that bind beings to the cycle of Samsara (rebirth).

III. The Path to Arhatship: The Four Stages of Enlightenment

In the Theravada tradition (the dominant school of Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar), the path to becoming an Arhat is linear and clearly defined. It involves the systematic breaking of the Ten Fetters (Samyojana)—the mental chains that bind a sentient being to existence.

The journey is divided into four distinct stages of awakening.

1. The Stream-Enterer (Sotapanna)

This is the first breakthrough. A Stream-Enterer has had a glimpse of Nirvana and has "entered the stream" flowing inevitably toward enlightenment. They are guaranteed to become an Arhat within seven lifetimes at most. They have eradicated the first three fetters:

- Self-view: The belief in a permanent, unchanging self or soul.

- Skeptical Doubt: Uncertainty about the efficacy of the Buddha's path.

- Attachment to Rites and Rituals: The belief that mere ceremonies can lead to liberation.

2. The Once-Returner (Sakadagami)

Having deepened their insight, the Once-Returner significantly weakens the grosser forms of:

- Sensual Desire

- Ill-will/Aversion While these fetters are not yet broken, they are attenuated. This being will be reborn in the human realm only one more time before attaining full liberation.

3. The Non-Returner (Anagami)

The Non-Returner has completely eradicated the fetters of sensual desire and ill-will. They no longer experience sexual attraction or anger. Upon death, they are not reborn in the human world but arise in the "Pure Abodes" (high heavenly realms), where they will attain Arhatship.

4. The Arhat (Arahant)

The final stage requires the destruction of the five "higher fetters," which are subtle and deep-rooted:

- Craving for fine-material existence (desire to be reborn in heavenly forms).

- Craving for immaterial existence (desire to be reborn as pure formless consciousness).

- Conceit (The subtle sense of "I am").

- Restlessness (Subtle mental agitation).

- Ignorance (Avijja - not knowing the Four Noble Truths).

When these are gone, the mind is pure. The Arhat has "laid down the burden." The cycle of birth and death is ended.

IV. The Psychology of the Arhat

What is the mind of an Arhat like? It is difficult for an unenlightened person to comprehend, but Buddhist texts provide descriptions of their psychological state.

The Cool State

The Arhat is often described as being "cooled." The fires of passion, aggression, and confusion have been extinguished. This does not mean they are catatonic or emotionless; rather, they are free from reactive emotions. They experience physical pain, but they do not suffer from it mentally.

"He feels the sensation, but he does not cling to it. He views the world with wisdom, like a man watching a play, knowing it is a performance."

The Six Constant Abidings

An Arhat interacts with the world through the "Six Constant Abidings." Whether they see, hear, smell, taste, touch, or think, they are:

- Neither pleased nor displeased.

- Equanimous.

- Mindful.

- Fully aware.

Functional Action (Kiriya)

For normal beings, actions create karma (cause and effect). For an Arhat, their actions are merely functional. Because there is no "self" claiming the action, and no desire driving it, their deeds leave no karmic residue. They act out of pure compassion and wisdom, responding to the needs of the situation perfectly.

V. The Great Divide: Theravada vs. Mahayana Perspectives

The concept of the Arhat is the central point of divergence between the two major branches of Buddhism: Theravada and Mahayana (which includes Zen, Tibetan Buddhism, and the traditions of Korea, China, and Japan).

The Theravada View: The Final Goal

In Theravada, the Arhat is the ideal. The Buddha himself was an Arhat (though a "Samma-Sambuddha"—a self-enlightened one who teaches others). The goal of the practice is to follow the Buddha’s instructions to become an Arhat and end suffering. There is no higher state of liberation than the destruction of the fetters.

The Mahayana View: A Resting Station

Mahayana texts, such as the Lotus Sutra, present a different perspective. They argue that while Arhatship is a noble achievement, it is not the ultimate perfection.

- Critique: They suggest the Arhat seeks personal liberation (saving oneself), which they view as a subtle form of selfishness.

- The Bodhisattva Ideal: Mahayana proposes the Bodhisattva as the superior ideal—a being who delays their own final Nirvana to stay in the cycle of rebirth and save all sentient beings.

- Reconciliation: In many East Asian traditions, the Arhat is seen as a "saint" worthy of respect, but one who eventually must enter the Bodhisattva path to become a fully enlightened Buddha.

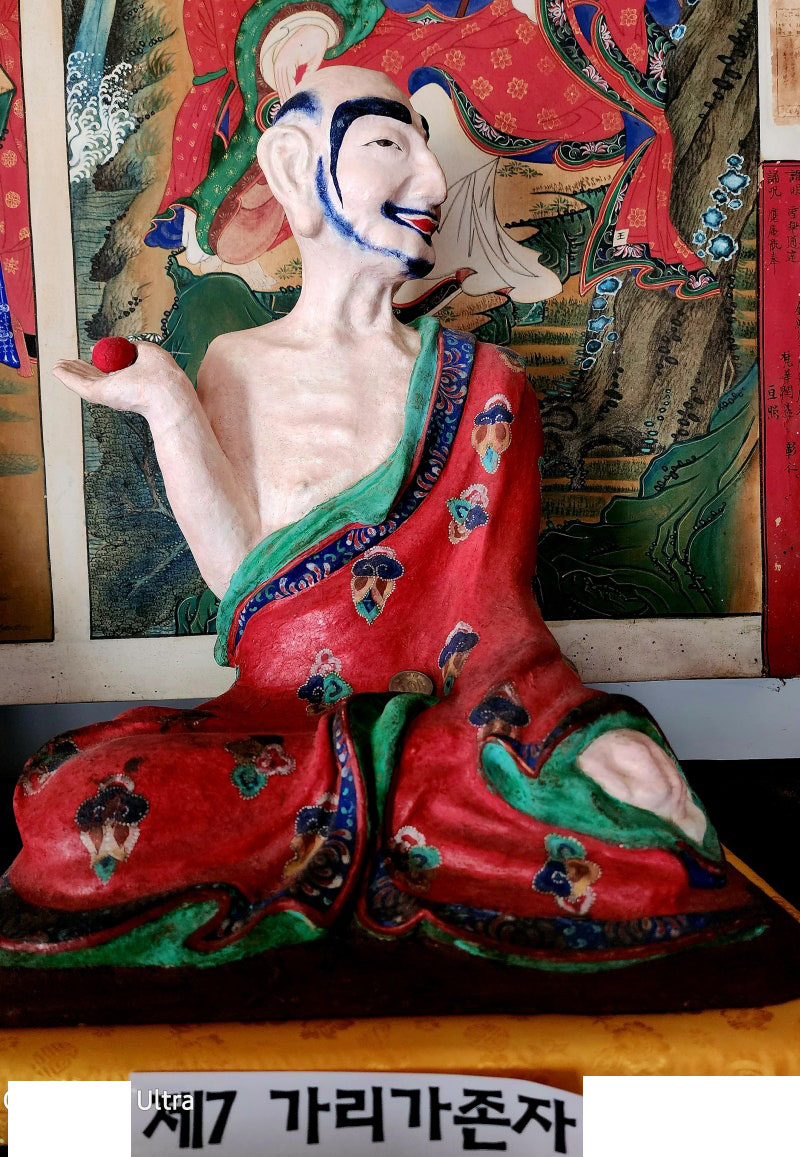

VI. Arhats in Culture and Iconography: The 16/18 Lohans

Despite the Mahayana critique, Arhats (known as Luohan in Chinese, Nahan in Korean, Rakan in Japan) are deeply venerated in East Asian Buddhism. They are viewed as guardians of the Dharma who possess supernatural powers and distinct personalities.

The Eccentric Saints

Unlike the serene, idealized features of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, Arhats are often depicted in art with highly realistic, unique, and sometimes grotesque or humorous features.

- Symbolism: This represents their humanity. They were distinct individuals with different backgrounds—kings, barbers, warriors, scholars—who all found the same truth.

- The 16/18 Arhats: A famous grouping in art (such as the Nahan-do paintings in Korean temples). Each has a specific attribute (e.g., Pindola, the Arhat with long eyebrows; or the Arhat taming a dragon/tiger).

The 500 Arhats

Large temples often have halls dedicated to the "500 Arhats," representing the disciples present at the First Buddhist Council after the Buddha's death. In these halls, no two statues are alike. A famous folk belief says that if you look closely enough at the 500 faces, you will find the face of your father, or even yourself—symbolizing that anyone can attain enlightenment.

VII. Conclusion: The Legacy of the Arhat

The Arhat represents the ultimate victory of the human spirit over its basest instincts. Whether viewed as the final destination (Theravada) or a vital stage on the way to Buddhahood (Mahayana), the Arhat remains a powerful symbol of:

- Ethical Purity: Living without harming others.

- Mental Mastery: Total control over one's attention and reaction.

- Liberation: The possibility of total freedom from suffering.

In a modern world driven by consumerism, ego, and constant distraction, the image of the Arhat—content with nothing, peaceful amidst chaos, and sovereign over their own mind—offers a timeless and necessary inspiration.